Special thanks to /u/jason_abacabb and /u/2stupid over on Reddit for pointing out some discrepancies in the article! In particular, I had previously stated the wrong pH cutoff of 5.0 instead of 4.6, and there was a section about fermentation kicking off in 3 days that needed to be cleared up.

Botulism. For many, it’s the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about hobbyist homebrewing – so much so that I’ve had to convince many that fermentation is safe before they were willing to try something I’d made. Until now, however, I couldn’t really articulate why homebrewed alcohol isn’t likely to contain botulism – so I did a ton of research to figure it out.

Your homebrewed beer, mead, or wine is most likely NOT contaminated with botulism. The bacteria that produces the toxin cannot survive in the environment created by fermentation. Botulism in fermented food and beverage is so rare that you likely do not need to worry about it.

I’ve long known that botulism is not something worth worrying about with homebrewed alcohol. But for the longest time, I thought it was because of sanitization – and as a new brewer, many years ago, I was vigilant and obsessed in my sanitization, worried about contaminants and making people who drank my beer sick.

But more recently, I’ve been fascinated with the subject. If modern sanitization practices are all that keeps our homebrewed beer, mead, and wine safe, how were people not dropping left and right due to botulism and other infection from fermented beverages? How could wild fermentation work?

What I’ve learned from my deep dive into the subject is interesting. Sanitization has nothing to do with it! In fact, even the best sanitization practices cannot get rid of the C. botulinum spores.

The real thing keeping our batches safe is fermentation itself!

I’ll explain the whys and hows below, but in summary: if you have a successful fermentation, and produce an alcoholic batch, you do not need to worry about botulism or other bad bacteria – with a couple of very specific and very niche caveats, outlined at the bottom of this article.

It’s so rare that it might as well be impossible.

What Is Botulism?

Botulism is the dangerous toxin produced by the Clostridium botulinum bacteria.

I realize you didn’t come here to learn the specifics about how the Clostridium botulinum bacteria or the toxins that it produces work.

But you did want to learn how to prevent botulism or how to determine if it’s present in your homebrew. And to really understand that – and feel comfortable with your ability to prevent or discover botulism – it does really help to know a few things about the bacteria and its toxin.

C. botulinum reproduces via spores. The bacteria itself (and more importantly, the toxin it produces) are what you should be concerned about: the spores are harmless.

However, the spores are incredibly resilient! All of the things you do to protect your homebrew – using heat or chemicals to sanitize everything – kills the bacteria, but not the spores. Theoretically, the spores can start producing bacteria again once the wort or must has settled.

In practice, however, C. botulinum has a handful of very strict requirements for its survival. Any environment that does not meet these requirements is hostile to the bacteria, and it will not be able to survive and grow long enough to actually produce botulism.

- A protein-rich environment. The bacteria needs protein to grow. This is important: wort made from grain has plenty of protein, but musts made from honey or fruit do not.

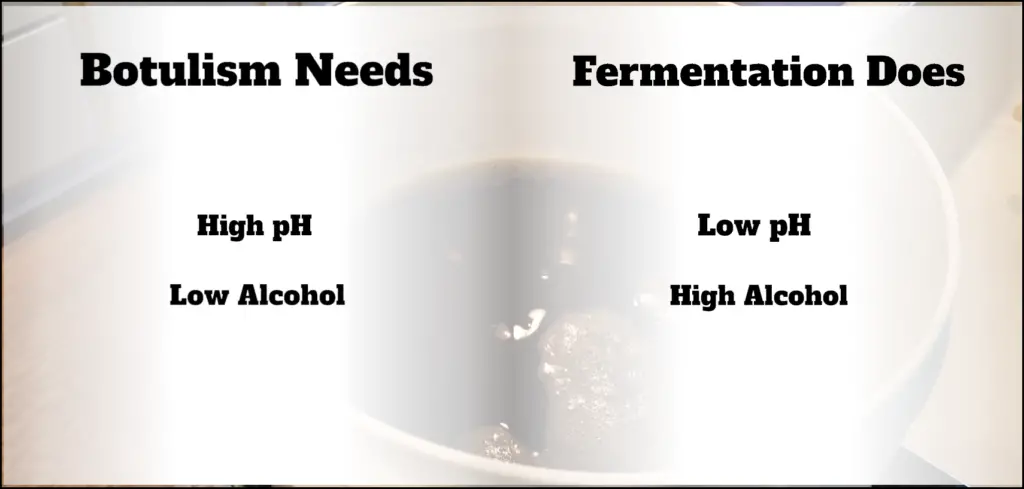

- A pH above 4.6. This one is key! Most solutions you work with in fermentation are far too acidic for C. botulinum.

- An oxygen concentration below 1%. The bacteria cannot grow in a wort or must that has been aerated.

Furthermore, it takes at least 3 days from the time C. botulinum is produced from spore to the time it is able to produce the toxin. Therefore, even if you produce a wort or must habitable for the bacteria, as long as fermentation kicks off within 3 days, the effects of fermentation will suppress any microbes before they can do anything harmful.

Note: it was brought to my attention that the above statement isn’t super clear. You do not need fermentation to complete in 3 days – it really does just need to start.

There is no cutoff where the bacteria is alive and happy and producing toxin until a certain pH or alcohol %, and then it is suppressed after that point. It starts being suppressed even as fermentation begins, the pH starts dropping, and alcohol is being produced – and becomes further suppressed the closer the environment is to reaching low pH and high alcohol!

Furthermore, once fermentation starts, the environment changes fast. Within only a couple of hours, the pH and specific gravity can both drop dramatically. Even in a wort with a moderately high mash pH above 5.0, the post-boil pH will be lower, and once fermentation begins, it can drop below 4.6 in a very short time.

Will Botulism Kill You?

Botulism is incredibly dangerous. It is one of the most toxic substances known – far more harmful than even cyanide. Untreated, 50% of patients die; even with modern medicine 5-10% die. Those who survive often experience permanent disability.

So, yes, the botulism toxin is bad.

However, it’s important to note that it is the toxin itself that’s harmful: the C. botulinum bacteria, and even more importantly the spores, are harmless by themselves.

As long as the bacteria is killed off before the toxin can be produced, you have nothing to worry about.

And intriguingly enough: it almost seems like the fermentation process was tailor-made to prevent botulism!

Brewer’s yeast, in their natural processes to take over their environment, counter the needs listed above. They literally create beer, wine, and mead as a hostile environment for nasties like C. botulinum.

Botulism is an extremely rare illness under any circumstance – maybe a few hundred cases in the U.S. each year, mostly including infants (who are susceptible) and drug users sharing needles. That number is reduced even more dramatically when we’re talking about homebrew, since fermentation is a preservative measure that actively prevents botulism.

In summary: botulism is dangerous, but you really shouldn’t worry about it when it comes to homebrew.

How Do You Determine If Your Homebrew is Contaminated With Botulism?

Unfortunately, there is no sensory indicator that botulism is present in a given food or drink.

Unlike in the other articles about mold and pellicles, I can’t provide images or descriptors to show what a botulism-contaminated batch looks like.

Occasionally, the bacteria can cause putrefaction – so if your batch smells rancid (and it’s not due to active, ongoing fermentation, which does smell funny until it finishes) it may be worth being on the safe side and just dumping it.

HOWEVER, if you have a solid understanding of what sort of environment is necessary for the production of botulism (listed above), and how fermentation works, you’ll know with each batch you make that there’s no way the bacteria could have gotten a foothold!

Which is the purpose of this article, after all.

The Good News: Fermentation Prevents Botulism!

Throughout human history, before modern understanding of microbes and food preservation techniques, people were making fermented food and drink successfully – and they weren’t dropping dead from botulism left and right!

Furthermore, many cultures – both modern and historical – did not rely in some big FDA-regulated company to produce their beer and wine. Alcohol was typically produced in the farmhouse by the farmer himself, or in the kitchen, and drank only by the brewer’s family or town.

The fact is, fermentation was utilized back then for more than just getting drunk. It was the best preservation method humans had – and it worked very well!

Fermentation is almost tailor-made to prevent nasties like C. botulinum from taking a foothold and turning a food or drink rotten or toxic.

Your yeast actively counter nearly every one of the listed items above that the bacteria needs to survive.

Even if your wort or must starts out as a perfect environment for C. botulinum to thrive, fermentation quickly puts an end to that.

As fermentation goes on, the pH drops, ending up around 4.0 for beer and even lower for wine and mead. Additionally, the yeast creates alcohol – which is toxic to the bacteria!

The goal for us homebrewers is to give the yeast the best chance they have to ferment a batch effectively. Through sanitization, pitching a hefty amount of yeast, and providing a sugar- and nutrient-rich environment for them, we enable them to get a foothold and start fermenting quickly.

As long as the yeast start quickly enough, the pH will drop and the alcohol content will increase fast enough to prevent botulism! Remember, it takes at least 3 days for the toxin to start being produced – as long as the yeast are actively fermenting before then, you have nothing to worry about!

What If Fermentation Doesn’t Start Quickly?

There are some circumstances where the yeast are sluggish and don’t start quickly – usually due to abnormal or suboptimal procedure on brew day.

You might be hoping for wild yeast to take hold, or the yeast packet you used didn’t contain enough viable yeast, or the must wasn’t nutrient-rich enough for them to get started quickly.

Whatever the case may be, there are times when fermentation doesn’t kick off quickly enough. Could that lead to botulism? Should you dump the batch?

NO! Even if fermentation does not get started quickly, your batch is unlikely to be contaminated with botulism – outside of a very narrow set of circumstances.

Musts made from honey or fruit are already hostile to the C. botulinum bacteria before fermentation even begins. They start with a pH below 4.6, and even beyond that (if you did add ingredients that increase the pH) they do not contain the protein necessary for a C. botulinum colony to actually grow.

On top of that, you should be aerating your wort or must prior to pitching your yeast. As I’ve mentioned before, oxygen is not the enemy until after fermentation is complete. Your yeast need it!

And if the batch is properly aerated, C. botulinum cannot thrive until all of the oxygen is consumed – by the yeast, which produce alcohol as they consume oxygen, which then creates a toxic environment for C. botulinum.

Even wort, which (as shown by the list above) hits nearly all of the requirements to be a safe space for C. botulinum, is inhospitable to the bacteria if it has been properly aerated. Even splashing the wort into your fermenter or shaking it is enough!

Under What Conditions Should You Be Concerned About Botulism?

There are very few situations where you should be worried that C. botulinum take get a foothold on your batch and contaminate it with botulism.

And if you have even basic knowledge of botulism and fermentation, as listed here, you’ll probably know you’re creating a botulism-prone environment before you do it!

To tell you what those very specific situations are, it’s probably easiest to describe how they have actually happened in real life.

The only recorded incidents that I could find in my research where individuals were diagnosed with botulism as a result of homebrewed alcohol involved a handful of prison inmates making prison hooch – specifically from potatoes.

Potatoes, a grain, would produce a solution similar to wort – it would have a higher pH than if it were made from nearly any other sugar source, and would have enough protein for C. botulinum.

In addition, these prison inmates probably didn’t have access to brewer’s yeast: most likely they were forced to attempt a wild fermentation. This can be (and often is) done safely, and I will describe some additional methods of botulism prevention below, but suffice to say you probably shouldn’t leave a container of high-pH grain-based sugar water out for possibly many days to try and catch a wild bug.

On top of that, they would have had to not aerate the wort for C. botulinum to take hold.

Another example often cited that could lead to botulism is the Mountain Dew mead that Golden Hive made a while back – which kickstarted a whole new viral trend of soda-based meads, bringing new homebrewers into the fold.

Since Mountain Dew (and most sodas) have an unnaturally low pH (low enough to be problematic for yeast), in the video, it’s suggested to use a buffering agent (baking soda) to raise the pH above 4.6! This made a lot of seasoned homebrewers uncomfortable, resulting in this stickied post on /r/mead.

However, if you recall from our list above, there are a handful of requirements for botulism to be possible – not just a high pH! This must, made from Mountain Dew and honey, would also have lacked the protein for C. botulinum to be able to grow.

On top of that, he pitched a packet of dry yeast, and stated in the comments section of the video that fermentation kicked off within 24 hours – well within the 3 days the bacteria would need to grow and begin producing the toxin.

However, if you were to produce something even more doctored up than the above (by adding protein as well as a buffering agent), and it took 3 days before fermentation began, and you didn’t aerate it, only then will it be possible for you to have a contaminated batch.

That’s a lot of things you’d have to do to make botulism possible!

Extra Steps to Prevent Botulism in Homebrewed Beer, Mead and Wine

By this point in the article, you should be able to rest assured, knowing that for any batch of homebrewed beer, mead, wine, or whatever else you might make, it’s actually nearly impossible for it to become infected with botulism.

The yeast have made sure of that!

However, on the off-chance you want to produce a wort or must that meets the requirements for C. botulinum to thrive – and you’re not sure that fermentation will kick off in time – there are a couple of things you can do to protect your batch even further.

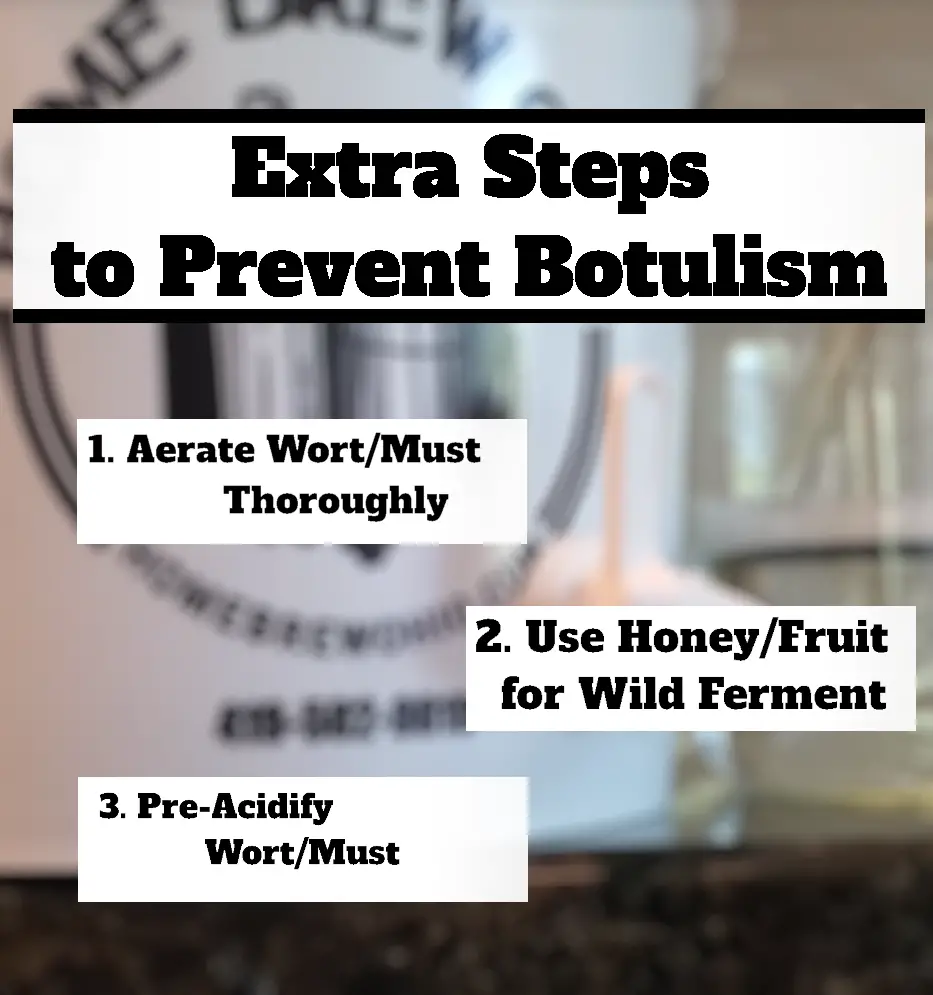

1. Aerate the Wort or Must Thoroughly

As stated above, C. botulinum needs an oxygen-free environment to survive.

If you create an oxygen-rich wort or must, that will protect it against contamination – at least until the yeast consume the oxygen.

But, again, the yeast will also be producing alcohol – so by the time your homebrew is depleted of enough oxygen for the bacteria, there will be too much alcohol, and it still can’t survive!

Plus, it’s good for the yeast. So you should be doing this anyways!

All it takes is to splash the wort or must around or to shake the fermenter vigorously. No special equipment necessary!

2. If Doing a Wild Ferment, Use a Honey- or Fruit-Based Starter Solution

While I can’t be 100% sure about this, I’m pretty confident that the prison inmates who suffered from botulism must have attempted a wild ferment with a high-pH, grain-based wort.

If you want to perform a wild ferment at home, I’d suggest not doing that.

It’s much safer to try and catch a wild yeast (or cocktail of yeasts and good bacteria) using honey and fruit. For one thing, honey and fruit already have yeast on them – so it makes it significantly easier to actually be successful.

Furthermore, as I’ve described already in this article, a honey- or fruit-based must cannot grow C. botulinum and other harmful bacteria due to the lack of protein and the low pH. So, even if it takes a few days (or weeks!) to catch a wild bug and get fermentation going, your must will be safe.

So, if you’re trying to make a beer (or similar grain-based product) from wild fermentation, it’s strongly suggested to use a small starter solution made from some combination of honey or fruit, and only once you’ve caught something, pitch it into your batch.

3. Pre-Acidify Your Wort (or Must)

The alternative to the above is to simply acidify your wort prior to pitching or catching yeast.

You can use a small amount of lactic acid (or other acid) to bring the pH down to a safe level, below 4.6.

Additionally, you’ll need a pH meter or pH strips to measure your wort and verify the correct pH. I strongly suggest a pH meter, but strips will do the job.

(You should probably get one of these and measure with each batch anyways – just to be completely sure! However, even though I know I should, I don’t do that…)

This will create an environment in the wort that cannot harbor C. botulinum and other dangerous bacteria, making it safe even before fermentation kicks off!

While a pH above 4.6 is beneficial to the end result when brewing any standard beer, remember that you’re using proper sanitization, aeration, and pitching an abundance of yeast into a controlled environment best suited for them – and that the yeast will take it from there and make your beer safe.

If you’re ever concerned about a batch or recipe – such as if you’re using a new outlandish process, performing a wild fermentation, etc – and you’re unsure about the potential for botulism, pre-acidifying it will protect your batch and ease your concerns.

Conclusion

It seems like, when anyone thinks about homebrew, the first thing that comes to mind is botulism!

But, as it turns out, that’s ridiculous. Your chances of getting botulism from a fermented product – homebrewed or commercial – are much lower than your chances of getting it from literally anything else.

Fermentation is the preventative measure for botulism.

So, now, armed with knowledge on the subject, you can rest assured – and keep brewing, knowing that you’re safe.