How often have you bought everything you’ve needed for a recipe, and then you weren’t able to get around to making it for a period of time? And how many times have you considered buying ingredients in bulk to save on costs, but you weren’t sure how quickly you could use them up? I’ve previously written about storage of grain, hops, and even liquid yeast, but what about dry yeast?

Factory-sealed, unopened dry yeast will theoretically remain viable and usable for up to two years when stored at room temperature and up to 5x that time when refrigerated – but many brewers report success even after much longer storage times. After opening the package, the yeast must be resealed and refrigerated.

If you are planning on using your dry yeast within any reasonable amount of time after purchasing it, you can just keep it at room temperature with the rest of your brewing equipment.

And “reasonable” is a pretty lengthy amount of time!

I think Chris White’s statement of “two years” of usability is extremely conservative. Some brewers have reported much longer storage times. I, personally, have used dry yeast that has been sitting around for up to four years!

However, dry yeast will absolutely last much longer when refrigerated – according to White, up to 5x longer!

So, if you do expect to be holding onto some of those yeast packets for an extended period of time, you’re probably better off keeping them in the refrigerator.

Plus, refrigerated yeast will just be more viable, with a larger, healthier starting colony at pitching. This means a healthier, stronger fermentation, with less stress (and thus fewer off-flavors) and a shorter lag time.

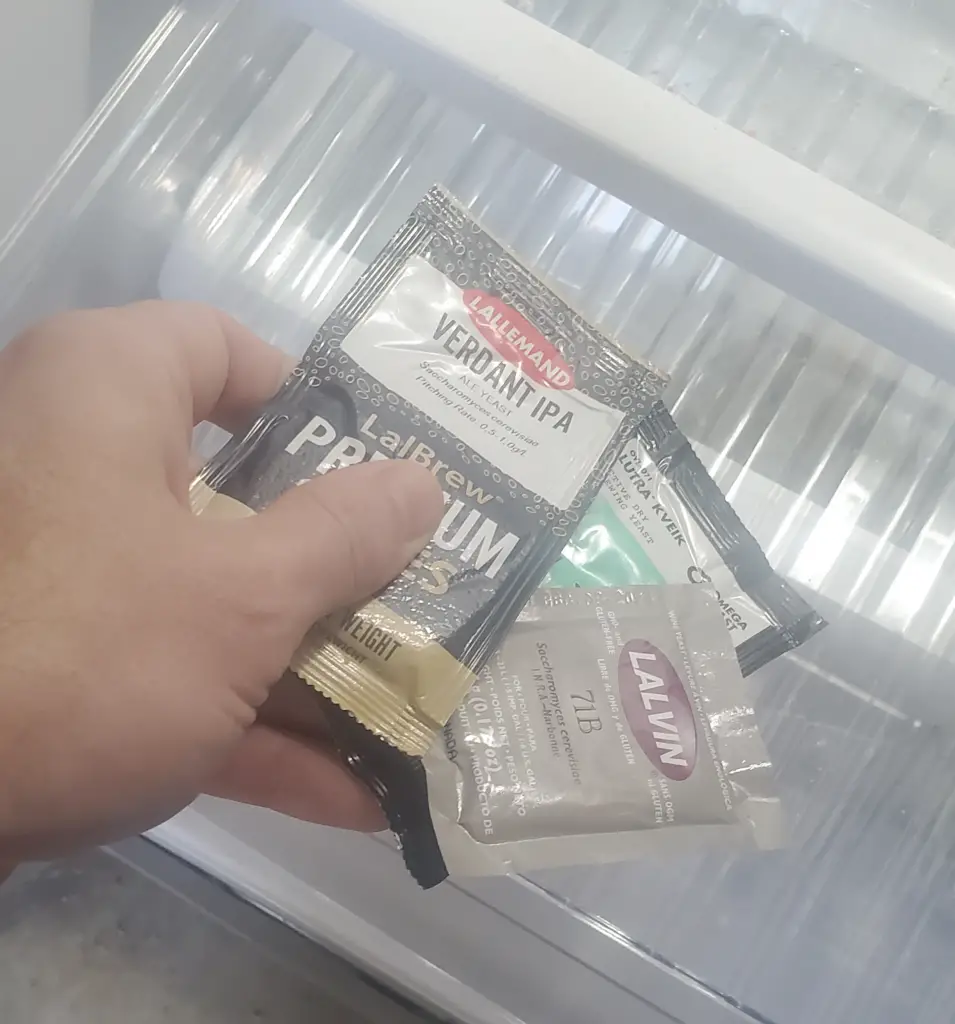

However, I typically just toss my extra packets of unopened dry yeast into a drawer in a closet where I keep my other brewing stuff. That drawer has plenty of extra yeast at any given time… and, given my tendency to try new things a lot, I end up accumulating a bunch of different kinds that don’t get used very often.

But, when I do get around to using them, fermentation kicks off just fine. I’ve never had a fermentation not get started due to a bad packet of yeast.

In fact, just earlier this year, I pitched a packet of Red Star Champagne yeast that I’d originally purchased in 2020 into a raspberry mead and it went great. That’s four years of storage time – not to mention two moves in that span!

Is that 100% optimal? Probably not. Refrigeration would have helped that yeast along better, I’m sure. Did it work? You bet!

What are the Concerns When Storing Dry Yeast?

There are only a few things to consider when coming up with how you plan to store extra dry yeast packages:

- Time. As time goes on, yeast cells will continue their metabolic processes and eventually die. With enough time, even more will die – eventually resulting in a depleted colony that will struggle to get going again.

- Temperature. The lower the temperature, the slower and more sluggish the yeast cells are; the higher the temperature, the more active the yeast cells are (even in a dried state). At very low temperatures, many of the yeast cells will fall asleep and become dormant, and at very high temperatures, yeast cells will die outright due to extreme temperatures.

- Moisture. Rehydrating yeast cells – whether on purpose or by unintentionally getting moisture into the package – will result in the cells “coming back to life.” Without fermentation to perform, their metabolic processes will occur very quickly and they will die off far faster than they would in their dried state.

Moisture is a non-issue if you are dealing with unopened, factory-sealed packages of dried yeast: the entire purpose of the packaging is to protect against moisture!

However, if you’ve opened the package, moisture becomes the primary concern, very quickly compounding the problems of the other two (time and temperature). Opened packages of dried yeast have their own storage requirements and need to be handled differently.

(I’ve also written a separate article about storing opened packets of dry yeast!)

Time and temperature are really all you need to worry about when storing brand new, unopened packages of dry yeast.

The yeast inside will remain viable, and the package, usable, for a long time – and that time is increased as the temperature in storage is lowered!

Be careful, however: while freezing temperatures can (in theory) really extend the lifetime of the package, in practice, any moisture in the package will freeze and, as the ice crystals expand, they can tear apart yeast cells. I’ve seen it strongly recommended by yeast manufacturers (such as White Labs) that you don’t store your yeast at or below 33°F for this reason.

(Although, in its original packaging, there should be little to no moisture inside – that’s the point – so you might be able to get away with it. Personally, I stay away from storing my yeast at freezing temperatures.)

Buying Dry Yeast in Bulk

Most of the time, you’ll probably just be purchasing individually-sealed packages of 11g of dry yeast in a given strain – these are good for one 5 gallon batch, which makes it a pretty standard purchase.

You can save some money by buying in what I’m going to call “semi-bulk,” where you buy several of a single strain of yeast. They’ll usually come as a single purchase, maybe in a container, of something like 5 individual packages of dry yeast.

This is typically how I make my purchases. If I need a yeast strain for a recipe (one that I don’t have on-hand already), I’ll get a pack of 5 or 10 (or whatever’s offered) at a time, even if I only need one. Then, I’ll have a few on-hand if I ever want to use that strain again – and I can save a bit of money on a per-batch basis!

The consideration, however, if you’re planning on doing this: you should actually use that strain again! Sometimes, I’ve left dry yeast sitting in my drawer for a long time… resulting in wasted money!

(Although, remember, dry yeast can last for years if unopened, so there’s always a chance to use it again in the future!)

If you find yourself using a specific strain often, it can be worthwhile to buy in much larger 500g packages and actually measure your yeast out by weight for each batch.

I actually do recommend this for new brewers, mead-makers, and wine-makers: rather than experimenting with a bunch of different strains, just get one all-purpose, beginner-friendly strain, such as Kveik (Lutra or Voss) or EC-1118. Focus on improving your knowledge and skills without too much variance from batch to batch, and branch out once you feel confident.

Of course, if you buy a much larger package of yeast, it will need to be refrigerated once opened.

Storing Unopened Dry Yeast at Room Temperature

Storing your packets of dry yeast at room temperature is probably the easiest thing you can do.

You probably have plenty of drawer space (and these packets aren’t very big) yet fridge space is often a concern.

While dry yeast does store better in the refrigerator, and if you have the option to do so then you probably should, it’s perfectly fine at room temperature for a long time.

How Long Does Yeast Remain Viable at Room Temperature?

According to Chris White of White Labs, as written in his and Jamil Zainasheff’s book, “Yeast,” packets of dry yeast should maintain viable colonies and remain usable for 2 years.

However, I’m pretty convinced this is an extremely conservative take.

A dry yeast packet will typically lose about 20% of its viable cells each year at 75°F. So, after one year of storage, you’ll theoretically only have 80% of the original colony left; after the second year, 64%, and so on. After four years in storage at room temperature, your dry yeast packet will only be about 50% viability.

64% of the original colony (after the theoretical two year limit) should be enough to produce a healthy fermentation – but the question is how healthy? You still have plenty of cells, and they will happily repopulate until there are enough of them to do the job.

The longer that the packet is stored, the more the yeast will need to work to build back up to a full colony. This can result in longer lag times before you start to see signs of fermentation as well as stressed yeast colonies, particularly if you’re using older packets with fewer viable cells.

However, remember that these numbers are a result of the observations of manufacturers like White Labs over time and represent averages, too.

There have been so many reports on forums like Reddit and HomebrewTalk.com, not to mention my own observations, reporting successful fermentations even after five, ten, or fifteen years in storage!

Would these have been stronger, healthier fermentations if the yeast was fresh or kept refrigerated? That’s likely. But they worked, nonetheless.

Should You Refrigerate Your Unopened Dry Yeast?

If you can, you should always refrigerate your dry yeast!

Dry yeast (and yeast in general) will survive much longer at refrigerated temperatures.

However, this statement is made in a vacuum. It’s a lot easier to store yeast at room temperature for most brewers, and that’s exactly what most of us do.

There are definite advantages to refrigerating your yeast, but it’s probably not very necessary for most of us – particularly if you intend to use the packet soon!

How Long Does Yeast Remain Viable at Low (Refrigerated) Temperatures?

According to Chris White, packets of dry yeast will only lose about 4% of the colony per year when refrigerated. This is five times slower than at room temperature!

A packet of dry yeast, stored in the refrigerator for one year, will still have nearly all of the original colony left.

At the end of those same four years mentioned earlier, the packet will still have 85% viability! Compare this to the halved viability at room temp.

Even after ten years, at 66% viability, most of the original colony still remains, and it takes more than fifteen years to cut the original viability close to 50% when the packets are refrigerated and unopened!

Beyond the benefit of improved health, not stressing the yeast, and keeping lag times low, you should really be storing your yeast in the refrigerator if you plan on holding onto those packets for a long time.

What Can You Do About Old Dry Yeast Packets?

If you find yourself in a situation where you’re stuck with a very old packet of dry yeast and you’re not sure how viable it is, you have a couple of options.

1. Rehydrate the Yeast Before Pitching

Rehydrating your yeast prior to pitching is a great way to quickly verify that the yeast are still viable.

Once rehydrated, they should begin visible activity, even if you simply rehydrated them with water and there are no sugars present. Fermentation isn’t happening, but they are waking up and their metabolic processes are starting up again.

Ideally, you should be rehydrating your yeast every time anyways, to ensure you didn’t get a dud packet and to give them every chance to have a happy, healthy fermentation.

But to be honest, I don’t do that. I really only rehydrate yeast when it’s a particularly old packet or I’m otherwise unsure of viability.

2. Salvage the Colony With a Starter

Even if your colony’s cell count is incredibly low, you should be able to salvage what’s left with a yeast starter.

The yeast starter, done right, will give the few leftover cells an optimal environment to reproduce without needing to worry about fermentation.

By using a starter, you can build the cell count back up to the necessary number to have a healthy fermentation.

However, when it comes to dry yeast, it’s usually strongly recommended not to use a starter. The process of producing dry yeast is supposed to result in a very hardy, healthy culture, straight from the lab – and a suboptimally-made starter could result in a weaker colony or even contamination.

So this is probably a last resort when dealing with dry yeast. If you have a packet that’ll work, you probably don’t want to do this!

3. Just Use More Packets

Each 11g packet of dry yeast is designed to contain a large enough colony to quickly start a very healthy, active fermentation in a standard 5 gallon batch at an original gravity of roughly 1.060.

For non-standard batches, it’s always recommended that you adjust your pitch rate accordingly. For example, a 2.5-gallon batch would require exactly half of a packet; a 10-gallon batch would require two packets. For very high-gravity recipes, you would want to pitch more packets, as well.

We can do the same thing when dealing with older packets that have lost their viability.

If you’re using a packet of dry yeast that has sat in storage at room temperature for four years, it may have lost nearly 50% of its viable cells.

However, if you want to brew up a full 5-gallon batch with this yeast, you might want to pitch two packets! Two packets of a given yeast, at 50% viability, will result in the same cell count as a fresh packet with 100% viability!

Alternatively, you might set that packet aside and use it for a 2.5 gallon half-batch. For a half batch, a packet with half of the original viability should be perfect. Just pitch the whole thing, instead of half as you would with a fresh packet!

Conclusion

Dry yeast is probably the easiest ingredient to store in all of homebrewing (or mead- or wine-making).

You can really just toss unopened packets of dry yeast into a drawer and forget about them for months – or even years!

However, for optimal storage, and to ensure the healthiest fermentations, you really ought to be keeping your dry yeast refrigerated – if at all possible.

(But none of us homebrewers seem to do that, and it works out just fine, so don’t stress too much about it!)