Oxygen is the enemy of a good homebrew, right? That is the concept that is beaten into new homebrewers learning the basics on the internet. However, it is much more complicated than that. I was recently asked this question on Reddit and, after writing up a detailed response to that user, realized that I could provide a better, more detailed answer here!

Oxygen is desirable at the start of fermentation, but if introduced afterwards, can ruin your homebrew. You should aerate your wort or must at the start of fermentation for best results. However, if oxygen touches your brew for even a moment once fermentation is complete, it can oxidize the batch and ruin the flavor.

Basically, the answer is: oxygen is desirable before and during fermentation, but is detrimental to your brew after fermentation is complete.

How Come Yeast Need Oxygen, Yet Oxygen Is the Enemy?

While brewer’s yeast is perfectly able to undergo fermentation and produce alcohol without oxygen, it does a much better job if oxygen is present both before fermentation begins and while it is happening.

Yeast doesn’t need oxygen to perform, but it does need it to thrive. Much like yeast nutrient, oxygen helps the yeast do what they need in order to grow, reproduce, and make alcohol. It makes for a much healthier fermentation. Without oxygen, the yeast struggle to maintain their cell walls and organelles, which can result in poor attenuation and off-flavors.

A well-aerated wort or must produces a higher quality end product.

Once fermentation is completed, however, oxygen is the enemy!

We’ve all heard about this – and I’d bet that most or all of us have experienced it: OXIDATION!

Oxidation occurs when a fermented beverage is exposed to air. It triggers a number of chemical reactions that turn the alcohol and other desirable compounds in the brew into very undesirable compounds (such as acetaldehyde). It affects both the appearance and flavor of the brew, turning it into a muddy brown color and producing many off-flavors that can come across as grassy or like wet cardboard.

If acetobacter is introduced – and it’s in the air – it can also turn the alcohol into vinegar!

Unfortunately, the oxidation process can happen the instant oxygen touches your brew. The chemical reactions can start immediately, and without yeast activity to remove the oxygen molecules from solution, oxidation can occur quickly. Once oxidized, the brew is unsalvageable – nothing can remove oxidation from a brew.

You can still drink it. It’s not toxic, and isn’t always the worst-tasting, but it isn’t the best, either.

(I’ve had to drink plenty of my own oxidized brews in the past!)

The key to producing a healthy fermentation, and a quality product, while avoiding oxidation is as follows:

- Aerate your wort or must well – before fermentation begins! Most homebrewers don’t have any fancy equipment for this, so we simply try to vigorously pour the wort or must into the fermentation vessel to create as much splashing as possible, or we shake it up really well.

- Once you have added the yeast, seal up your brew and DO NOT open it again! Pop on your airlock, blowoff tube, spunding valve, or similar pressure relief item, and do not let outside air touch the brew until it is in your glass and you are drinking it. Obviously this is very difficult without special equipment, so as homebrewers, we often have to simply try our best.

More on these steps in the sections below.

Oxygen Before Fermentation Begins: Aerating Your Wort or Must

We have established that introducing oxygen to your brew early on is good. Your yeast need oxygen to do their job well.

Open fermentation is, of course, an option, and is something I’ll touch on in the next section. However, in modern brewing (both homebrewing and in a professional or commercial setting), open fermentation is little more than a gimmick. It’s something we might play around with for a certain batch (or a certain line of beer at a brewery) just to call back to the way things were done in the old days, or for the sake of experimentation.

Nowadays, we tend to follow a different brewing pattern: add oxygen to the wort or must prior to pitching the yeast, then seal up the fermenting vessel and don’t add any more oxygen for the duration of that brew’s lifetime.

There are a few different ways to get that oxygen into the brew, but the most common amongst homebrewers is just to shake it up really hard.

And that’s a fine way to do it. I still do it to this day. It makes good alcohol, and it’s free.

However, if you’re willing to splurge, those who have upgraded to better equipment swear by it. It produces a very noticeable difference – a much cleaner fermentation and a better end product. Those who have tried it will never go back to the shake method.

The thing is, simply shaking the fermentation vessel cannot introduce enough oxygen into the wort or must, no matter how hard or how long you shake it!

In Chris White’s (yes, the one from White Labs) book, “Yeast”, he strongly suggests that wort have at least 10 ppm of oxygen dissolved in solution, with 12 ppm being far more desirable. The book focuses on beer brewing, but this applies to wine and mead musts, as well – after all, we’re all using brewer’s yeast. In fact, for higher gravity brews like imperial beers, wines, and meads, the yeast need even more oxygen to be happy!

However, by just shaking the brew, the most you can get is 8 ppm, and that’s if you shake it really, really hard. It’s unlikely you’ll get anywhere close to that. Based on Chris White’s observations in his book, most brewers only get around 4.5 ppm from shaking – that’s less than half of what you need!

Using an aquarium pump will get you the 8ppm consistently, but it still only uses ambient air – it can’t get any more than that.

So how is it possible to get the necessary amount?

Well, commercial breweries inject pure oxygen into the fermenting vessel – in much the same way we inject pure CO2 into our finished beer when kegging.

Today, oxygenation kits and oxygen tanks are readily available on the market, but they are a bit pricier.

Honestly… I’d suggest simply using the shake method if you are new to the hobby. However, I will likely be upgrading to a pure O2 setup at some point myself. It seems this, along with fermentation temperature control and other things to optimize the fermentation step are by far the best way to spend your money on the hobby – the low-hanging fruit that produces the best brews with the least investment.

Hot Side Aeration

Hot side aeration is a very controversial topic, and currently there seems to be no clear answer on whether it is really a problem or not. For that reason, I won’t delve too deep into the subject, but I will just touch on it briefly so you can make up your own mind.

Essentially, the argument is that, at hotter temperatures (i.e. when mashing or boiling your wort), oxygen introduced will chemically bind to the molecules in solution. The oxygen that does this cannot be boiled off, and cannot be used by the yeast, causing it to remain in the brew even after fermentation – and leading to oxidation.

For a long time, this was held as absolute truth, but more recently, some homebrewers are calling it a myth. From what I understand, more experimentation and study is needed to come up with a concrete answer.

What does it mean for us? Well, I guess, to be on the safe side, just hold off on aerating your wort (or must, if you’ve heated it) until it is chilled to pitching temperature.

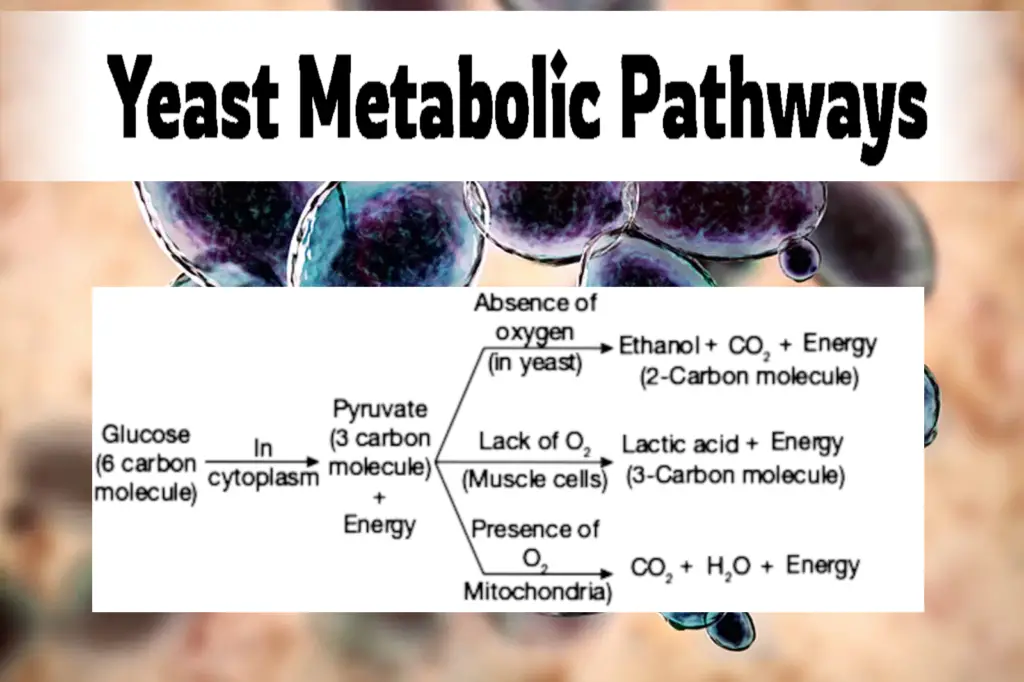

Oxygen During Fermentation: Yeast Metabolic Pathways

So why is it that we even want to add oxygen to the process? If oxidation of the end product is such a horrible thing, why even risk it, when the yeast can produce alcohol without oxygen anyways?

I’m not going to go too deep into the inner workings of a yeast cell in this article, but I think it is important to discuss the actual science – the biology and chemistry – of how yeast actually produce alcohol (and specifically how oxygen is important in that process) in order to properly answer the question.

Many newbies (those who haven’t studied microbiology at all) may not realize this, but yeast actually have two metabolic pathways, or ways to convert food into energy: an aerobic one (which requires oxygen) and an anaerobic one (which occurs when oxygen is not present).

The anaerobic (lacking oxygen) pathway primarily produces alcohol, but the aerobic (requiring oxygen) pathway is far healthier and more efficient for the yeast.

It’s especially important for the yeast to have access to oxygen (as well as other nutrients, such as nitrogen) during the growth phase. At the start of fermentation, before it gets really vigorous, the goal of the yeast culture is actually to grow. Yeast utilize oxygen and nutrient to reproduce until they have a large enough colony to actually start active fermentation.

If you deprive the yeast during this phase, they won’t be able to produce healthy new yeast cells, which will impact the fermentation before it even begins.

Additionally, yeast will continue to uptake oxygen all the way through active fermentation. As long as fermentable sugars are present, yeast will continue to grow, reproduce, and make alcohol – and all along the way, having access to oxygen, nitrogen, and other nutrients will help the yeast do so while maintaining their health and happiness.

This results in a clean and efficient fermentation, allowing the brew to attenuate fully – meaning all sugars are consumed and you get the desired ABV from the brew – as well as reducing any off-flavors that the yeast would otherwise produce if it becomes stressed.

That’s why you need to add oxygen to your wort or must – to keep your yeast happy and to produce the best quality product you can!

A Discussion on Open Fermentation

Open fermentation basically means leaving your fermentation vessel open during active fermentation.

During active fermentation, while the yeast are producing alcohol and throwing off tons of CO2, and the brew is foaming vigorously, the liquid is actually mostly protected from the air. Not only is CO2 denser than air, sitting atop the brew as a sort of protective barrier, the pressure from fermentation will push air and most contaminants forcefully away from the brew.

However, any amount of oxygen that does make it into the brew can actually be beneficial. As long as the yeast is still fermenting away happily, it will consume any new oxygen molecules that end up in solution. This can result in the yeast actually being happier during open fermentations compared to the closed fermentations we’re used to.

That’s the theory, anyway. I have no personal experience with open fermentations.

Just be sure, if you do perform an open fermentation, to transfer the brew to a closed vessel before fermentation is complete! It’s suggested to make the transfer after high krausen, when the foam has fallen to about half of its peak size.

You do not want to be too late! If you wait until fermentation is over, you’ll risk exposing the brew to oxygen when the yeast are no longer willing to consume it. You might even end up with leftover oxygen that was introduced before fermentation was complete, but so late that the yeast did not get around to using it all!

Oxygen After Fermentation: Oxidation

It’s kind of a funny view into life: oxygen is such an important and necessary part of life, yet it degrades everything it touches.

The common misconception is that oxygen is bad because it has something to do with stressing the yeast and causing them to produce off-flavors. However, this is completely wrong. It’s only once the yeast are no longer involved that oxygen becomes a problem.

Oxidation is the result of chemical reactions (as opposed to biological ones) between oxygen and the various molecules (alcohol, carbohydrates, proteins, etc.) that make up the brew. The oxygen molecule comes into contact with these other molecules (the ones that we want, that produce desirable flavors and sensations), turning them into something different – something that tastes bad or gives a bad sensation.

And it can happen so easily! All it takes is a little bit of air to come into contact with the liquid, and the oxidation process begins immediately. That’s why it’s so hard for new homebrewers to combat.

Fortunately, there are ways to get around it.

To read more about oxidation and how to prevent it, check out this other article!

Some beverages and styles can easily mask the off-flavors from oxidation. Big, malty, roasty beers such as stouts and rich, tannic red wines can hide oxidation well. However, you want to be extra careful with oxidation when it comes to hoppy beers like IPAs and delicate, fruity meads and wines.

Avoiding oxidation is as simple as just not giving the brew a chance to ever come into contact with the air – but that’s easier said than done!

Closed transfers are your friend in this regard. If you can transfer the brew from one vessel to another (be it primary to secondary, or when bottling or kegging) without even opening either vessel, there’s no chance for oxidation.

If you are willing to pay for a more complex fermentation setup (with pressure-ready fermenting vessels and kegs), you can achieve perfect closed transfers easily. However, the sort of equipment you need for this kind of thing can get pretty pricey, and isn’t recommended for a beginner brewer.

Pressurized fermentation in the keg you intend to serve from is, of course, another solution. By fermenting in and serving from the same vessel, you eliminate the need for transferring the brew – and thus eliminate any chance for introducing oxygen.

Of course, the cheap route is to simply be extra careful during transfers. Use spigots and gravity instead of racking canes (which pump in air to create upward pressure out of the vessel) and don’t take the lid off of a vessel while liquid is still in it. This won’t eliminate the chance for oxidation, but it can drastically reduce it. I’ll expand on this in a future article.

Where It Gets Weird: Barrel Aging, etc.

It took me a long time and a lot of research to wrap my head around barrel aging beer and wine, and how to keep your brew from becoming contaminated or oxidized when doing so.

Oak barrels are watertight, but they are not airtight. It’s one of the things that makes them so useful when aging liquors like whiskey and rum: air and atmospheric pressure can force the liquor in and out of the oak staves, resulting in both flavor absorption and various chemical reactions inside of the wood.

But high-alcohol liquors aren’t prone to oxidation. Evaporation, maybe, but that’s another issue entirely.

Beer and wine, though? Oxygen is the enemy, right?!

Well, the answer is… it’s more complicated than that.

Certain brews and styles actually benefit from a bit of oxidation, if it is done right. Oak barrels, when sealed, allow oxygen to enter slowly and methodically over a long period of time. This results in a very, very slow oxidation process, which very subtly introduces some oxidation flavors.

Again, in certain brews, these subtle oxidation flavors, melded properly with the rest of the brew’s flavor profile, can work out magically. This is similar to how some other off-flavors are considered undesirable, or outright awful, in almost all circumstances… but are acceptable with very specific flavors.

Consider diacetyl: it is considered a horrible off-flavor, and when present, can sometimes cause a brewer who is sensitive to the flavor to dump the whole batch. However, in some beer styles such as heavier stouts, diacetyl is acceptable, and can even be desirable in very small amounts.

And when sour brews and wild yeast enter the picture, all bets are off – “best practices” are often thrown out of the window entirely when working with these brews!

Conclusion

In summary: oxygen is beneficial to your brew before and during fermentation, but your batch can be ruined entirely if it is exposed to the air after fermentation is complete.

Modern best practice is to get oxygen into the wort or must just before you pitch your yeast, and then seal the batch up inside the fermenting vessel with an airlock or blowoff tube – and don’t open it back up at all until it’s ready to drink!

Obviously this is very difficult to do completely without special equipment. However, if you’re looking to upgrade your equipment, you should be focusing on the fermentation side of things before the brew day: don’t buy that fancy Grainfather system before you have fermentation temperature control, an O2 injector, and you’re able to successfully perform closed transfers whenever moving your brews from vessel to vessel.

For further reading, check out “How to Brew” by John Palmer, and the “Yeast” book by Chris White. And, of course, it’s always beneficial for us homebrewers to do a deep dive into the nuances of the biology of yeast cells!