One of the most common questions amongst new homebrewers, when they see fermentation for the first time, is “is this contaminated?” While contamination is rare if you’re rigorous with sanitation, it can happen. One of the most common infections in both homebrewing and commercial brewing environments is wild yeast – but how do you tell if it’s there? And what do you do when you find it?

If your beer, mead, or wine has a very funky flavor or aroma, often described as horsey, barnyard, or sweaty, then it is likely contaminated with wild yeast. A white pellicle atop your brew is a good indicator of wild yeast. If your brew is infected with wild yeast, and there is no mold, it is safe to drink.

As long as you do not see signs of mold, your brew is safe to drink – and it’s easy to tell if it’s mold!

(For more information on mold contamination, including how to discern mold formations from other types, check out this other article!)

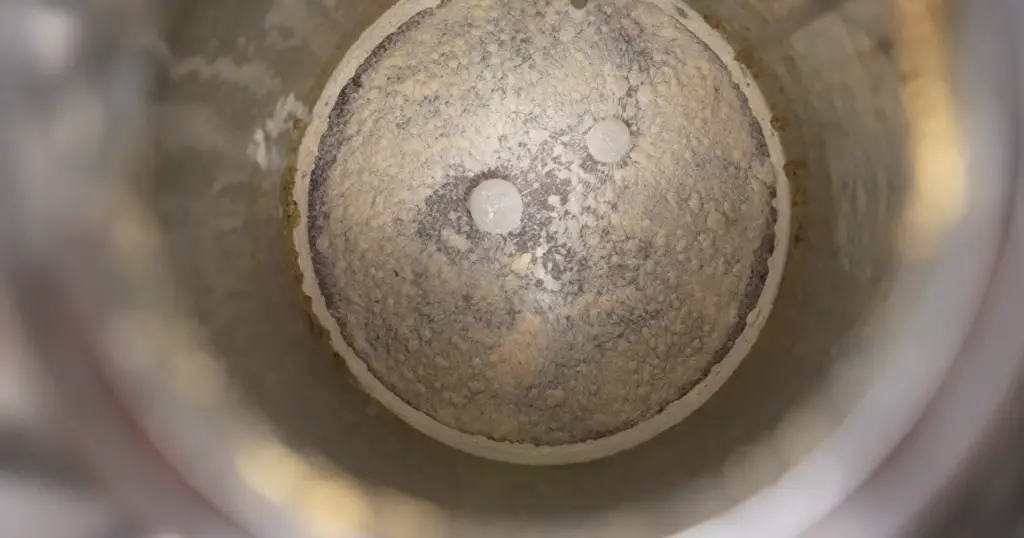

A thick, solid-looking, white pellicle is usually a sign of wild yeast. It’s often claimed that Lactobacillus can form a pellicle, but I’m not entirely sure of the truth to that.

This pellicle might appear gross, like something is wrong with your brew, but it’s not a danger to your health.

The biggest problem with Brettanomyces and other wild yeast is the flavor and aroma. Calling it an “infection” does not imply your brew is tainted in some way – it just means that the batch has gone wild and taken on a life of its own. Wild yeast can absolutely dominate the flavor profile of a batch, creating something wildly different from what you were intending or expecting.

Some of the things it can chew on are esters – the fruity, enjoyable flavor compounds that we often seek out from our yeast. This means it reduces the original flavors while creating its own!

It also has a wide range of very funky flavors. It can range from clove and spice to horse sweat and even vomit. That sounds pretty bad, doesn’t it?

Some people like a bit of the funk in their brew. Done right, it can really add complexity. Consider the flavors of smoke, medicine, moss, and even band-aid that often describes an Islay scotch. Now remember that some people consider this the pinnacle of whiskey, while others find it to be completely unpalatable, and many fall somewhere in-between.

Some people intentionally pitch Brettanomyces into their brew, seeking out this complexity!

Additionally, if you’ve ever had red wine… well, most red wine has some amount of Brett-iness, especially the ones aged in oak for extended periods of time!

This means that the batch can potentially surprise you and actually turn out quite good – or quite bad.. I suggest if your brew shows signs of wild yeast – a pellicle, a funky aroma – try it! It can’t harm you, and you might actually like it! If you don’t… well, at least you tried it, and you know for sure before you dump it.

What Is Wild Yeast (Brettanomyces)?

I’ll try not to go too far into the weeds here. I know you’re here because you’re worried about your brew, and probably aren’t too interested in learning microbiology at this moment.

Wild yeast is really any kind of yeast that can be found in the wild (that seems fairly obvious).

The thing is, yeast is everywhere. It’s on the skins of fruit, the bark of trees, the dirt, and even your skin right now (assuming you didn’t just stick your hands in your bucket of Star-San!). Of the many kinds out there, only a fraction of the strains is considered “brewer’s yeast,” but all of them function very similarly.

Comparing commercially-produced brewer’s yeast, used for brewing and baking, to wild yeast strains is a lot like comparing your dog to a wolf, coyote, or fox. They’re basically the same, but one has been domesticated by humans, trained to behave closely to exactly how we want them to.

The various yeast strains we cultivate for our ales, lagers, wines, etc. have been carefully (if historically almost by accident) crafted to produce the flavors and textures that we desire most in our brews. Today, big yeast labs take that even further, isolating individual cultures for release based on very specific characteristics.

On the other hand, what you get with wild yeast can be random and chaotic. Even when labs have tried to isolate strains of Brettanomyces to exert certain characteristics in a brew, the results can vary wildly, sometimes based seemingly on the whims of the yeast themselves.

Wild yeast can contain yeast from a variety of genera, including species of Saccharomyces that aren’t considered “brewer’s yeast” (and don’t behave the same).

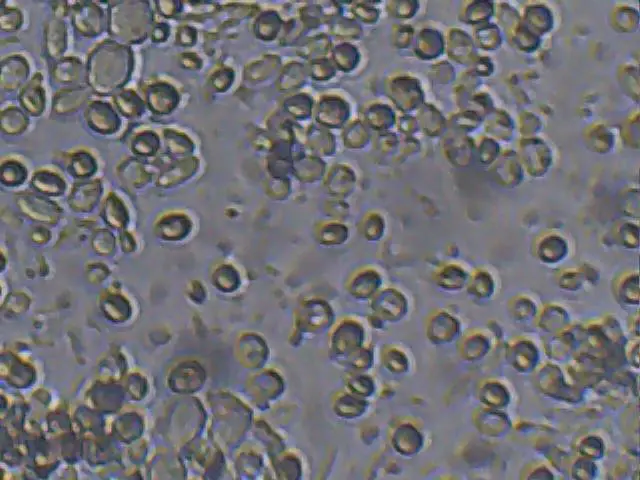

However, the most common yeast that infects our brews is Brettanomyces. This is a sister genus to Saccharomyces, and is functionally (if not entirely behaviorally) similar to brewer’s yeast. It’s the one that most often comes up when brewers talk about wild yeast infections.

There are a few key differences, though.

For one thing, Brettanomyces can actually consume almost every sugar – including the ones that our brewer’s yeast cannot. This means that, in an infected batch, after your chosen yeast has eaten everything it can and finished working, Brett will keep chewing through all of the unfermentable sugars and leave your brew bone-dry.

It even consumes wood sugars, which is why it’s often found in oak-aged red wines!

Brett also tends to take much longer to attenuate, and even longer to clean up after itself. I have read accounts of other brewers who have intentionally brewed Brett-fermented beers that took a couple of months to fully attenuate, and then almost a year for the Brett to continue to age the beer and clean it up!

Most Brett strains are pretty good at cleaning up, too. They like to chew on the esters that were produced by other yeast, as well as other compounds that some bacteria can throw off. For example, a brew infected by Pediococcus will have a very thick, ropy texture that can turn some off, but, given enough time, Brettanomyces can actually fix the texture entirely.

What this means is, if you end up with an infected batch that includes any combination of wild yeast, Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, and any others, and you don’t like the product today, just give it time! It may actually be really good if you’re patient enough.

How Do You Determine If There is Wild Yeast (Brettanomyces) In Your Brew?

I’ve seen a number of posts on forums and reddit asking the same thing: “Is my brew ok? Should I dump it?” and so many of the pictures are the same! I’ve honestly never had a (wild yeast) contaminated batch myself, but I’ve been fascinated by wild fermentation ever since I began brewing, and from what I’ve seen and read, it’s very obvious when your batch has a wild yeast infection.

The most obvious sign of a wild yeast infection is the pellicle that can form in a layer across the top of the liquid. This pellicle will be solid and white, and can form a complete layer or several chunks. It often is just a solid sheet, but can also have bubble-like formations or ripples throughout (see the image provided).

Mold would have a very different appearance. It would be fuzzy or furry, possibly white but could also be green or blue – it would look the same as any mold you’d see growing on a piece of bread or fruit! A pellicle, on the other hand, is solid and is always white.

If it’s fuzzy, dump the batch.

A pellicle may also be a sign of a souring bacteria, although that is not 100% certain. Pellicle formation isn’t very well studied and science doesn’t exactly know a lot about what it is or why it forms. We think that Lactobacillus and Pediococcus can sometimes form pellicles, but we know that many types of wild yeast, particularly Brettanomyces, do.

In truth, if you have an infection of one of these bugs, you probably have a combination of several or all of them. Brett often likes to run with Lacto and even Pediococcus and Acetobacter.

Aroma and taste are also strong indicators of a wild yeast infection. Brett and other wild yeast produce a wide range of flavors, wider than the narrow subset of flavors that brewer’s yeast has been carefully cultivated to produce.

This can include anything from spicy notes (which, granted, are sometimes found in Weissbier strains and other brewer’s yeast) to some really earthy and funky notes that are often described as horsey, sweaty, barnyard, and yes, even vomit.

Many species of wild yeast can also produce small amounts of lactic or acetic acid, but it’s not really what they’re known for.

This concept of “Brettiness” or wild yeast-induced flavor is very fluid. Depending on the yeast you ended up with, how much it dominated the strain you pitched originally, when in the process it was introduced to the batch, your ingredients, and even your own sensitivity to certain flavors, a contaminated batch could have various levels of funk. It could be absolutely dominated by phenolic flavors, or have just that hint of underlying funk that adds a bit of character.

Depending on what combination of flavors your contaminant felt like creating, your brew could end up very complex and interesting, or downright awful.

You Have a Wild Yeast (Brettanomyces) Infection: What Now?

What happens when your batch is infected? Is that the end? Do you just dump it right then and there?

If your batch of beer, wine, or mead is infected with wild yeast, it’s still safe to consume. It’s up to you if you want to dump it, but if you are brave enough, you should try it first. Even if it does not taste good, age and patience will give the batch time to improve, and you could end up with something great.

If you have determined that your batch is infected with wild yeast (and possibly other contaminants like lacto), and you are simply not brave enough to try it, no one will blame you. That’s the great thing about homebrew – you’re doing it for yourself, and you can do what you want!

In this case, feel free to dump it. In fact, many of these infected batches don’t turn out great. Breweries that specialize in spontaneous fermentation often need to blend batches of various ages to produce something worth selling.

However, some brewers seek out the funk. Adding a bit of Brettiness to dense red wine can really improve its character. Homebrewers can (and do!) purchase lab-cultivated strains of Brettanomyces and produce beer made 100% from “wild” yeast.

I have not yet had a wild fermentation happen to me, but if I did, I would definitely try it before I decided to dump it out. Then again, I’ve been fascinated with the idea of spontaneous fermentation for years – I just haven’t been brave enough to attempt it!

If you try it, and you don’t like it, you might still want to give it time to age before giving up. Brettanomyces can continue to attenuate far longer than brewer’s yeast, and will chew up everything from typically non-fermentable sugars to the byproducts of other microbes in the brew. This means that the flavor of the batch will continue to change and evolve over time, taking even up to a year before it’s truly ready to enjoy.

If you find it has aged to a point where you enjoy the taste, and you don’t want it to change anymore, you can take measures to stabilize the brew and lock in the flavor. Wine stabilizers, keeping the pH very low, and preventing exposure to oxygen go a long way, but you’ll definitely want to keep it cold to keep the yeast dormant.

If you’re bottling the brew, you’ll definitely want to keep it cold permanently (or until you drink it). Otherwise your wild yeast might keep attenuating and you’ll have bottle bombs!

Pasteurization is another option (and really the only one available to homebrewers to actually kill the wild yeast), but the process can also change the flavor.

More important than being concerned about your batch, however, is being concerned about your equipment. Brettanomyces is tenacious and can be extremely difficult to get rid of. That’s part of the reason it persists in many of your favorite commercial wines despite the wineries trying extremely hard to produce a cleaner flavor.

Wild yeast can live everywhere, and can permeate porous materials – most notably wood (many yeast species love to eat wood sugars) but also plastic, vinyl, etc. If any of these materials touched the infected batch, you can assume they’re contaminated for good.

Non-porous material such as glass and stainless steel is fine, however. This is one reason many breweries and wineries have switched to stainless steel equipment!

As far as what to do with your contaminated equipment? That’s up to you! Definitely don’t use it for another batch that you intend to be clean. If you prefer to be on the safe side and simply trash it, you are free to do that.

However, if the batch actually turned out quite nice, you could potentially use that equipment again for another “wild brew!” Just keep it far away from the rest of your equipment – unless that’s all you want to brew going forward.

Will a Wild Yeast (Brettanomyces) Infection Kill You?

If you’ve read up to this point, you should already know the answer, but let’s get to the heart of the question (and probably the reason you’re here). Is wild yeast hazardous? Will drinking a batch of homebrew infected with wild yeast make you sick? Will it kill you?!

No, a wild yeast or Brett infection in your beer, mead or wine will not kill you or make you sick. Wild yeast is not hazardous to your health. It is found everywhere, and functions the same as brewer’s yeast. If your brew is infected with wild yeast, you can drink it safely.

Wild yeast and brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae and similar) are functionally the same. The yeast that infected your brew does the same thing that the yeast you originally pitched was doing. The only real differences are that it might attenuate lower, throw off a different set of flavor compounds, and create a different texture in the final beverage.

Nothing that wild yeast does will harm you any more than brewer’s yeast would.

Even if the infection came along with Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, or similar, your brew is fine to drink.

Just make sure there isn’t any mold!

Conclusion

As far as contaminations go, wild yeast is a fairly common one. Often, a wild yeast infection really means it’s a cocktail of contaminants: some Brett, some lacto, maybe some Pediococcus. All of these (especially the Brett) can dramatically change the flavor, aroma, and texture of your brew from what you intended, but none of them are harmful.

As long as you don’t see mold, your brew is safe!

However, it may not be anything like you were hoping for. Try it and see! It may be awful and you have to dump it anyway, but it might just pleasantly surprise you.